Once upon a time

a monkey drank wine

on the streetcar line.

The streetcar broke

the monkey got choked,

and everybody went to heaven

except the big nanny goat.

Papa taught us the rhyme.

Us cousins, we gathered in the living room. Sometimes together, sometimes not; one of us sat in Papa’s lap as he told us stories, his voice looping and dropping and singing. Mama sat in her rocking chair, consistent as the sunrise, as she looked on with muted approval and vast contentment.

My favorite was the one about the monkey. I would sit on Papa’s lap, next to the lamp he’d welded before I was born, and demand the tale. “The one about the monkey.”

He’d begin with a rhyme: “Once upon a time….”

And I’d finish with a question: “Why did everyone go to heaven but the big nanny goat?”

There were other stories and rhymes coursing through the vibrant fabrics of our childhood––like the Little Colored Boy who turned on and off our TV in the middle of the night, and Peter Piper who picked peppers––but I always returned to the spectacular landscape of the streetcar line. Who was on it? Were they missed? How’d the streetcar break, anyway? Papa would laugh at my questions and give no answers.

It didn’t matter. I ate the questions just like I ate the rhyme. I never left my grandparent’s house hungry.

I was washing the dishes recently when the rhyme returned to me. I paused my chore with soapy hands to reach for my phone, eager to type the rhyme into a search engine and test my memory. Instead of finding one specific answer with the monkey and the wine and the billy goat, I found The Clapping Song.

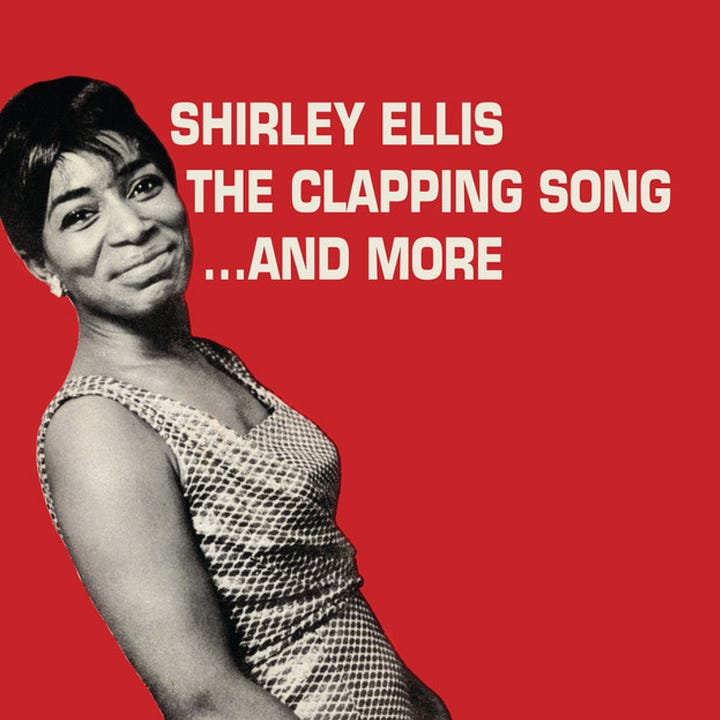

The Clapping Song, written by Lincoln Chase and recorded by Shirley Ellis in 1965 sold over a million copies; Ellis opens the song with the nursery rhyme, singing in an emphatic, matter-of fact tone: “Three, six, nine, the goose drank wine, the monkey chewed tobacco on the streetcar line.”

I frowned at my phone, soap suds falling, a Youtube video open. No, I thought. That’s not the rhyme. I searched and searched for the version with the nanny goat. I researched Ellis. She was born in the Bronx in 1929, while my grandfather was born in Clay County, Mississippi in 1927. Only two years, about a thousand miles, and a few different lyrics separated them.

I looked into the predecessor of The Clapping Song, which happens to be a song called Little Rubber Dolly (1930s) by Light Crust Doughboys, in which Chase and Ellis took the lyric: “My mother told me if I was goody that she would buy me a rubber dolly…”

My memory sputtered. Suddenly, I was 9-years old and shoving my sneaker into a circle of other sneakers, watching a brown finger tap the top of each one. Our hearts were racing as we watched. Tap. My. Tap. Mama. Tap. Told. Tap. Me. Tap. To. Tap. Pick. Tap. The. Tap. Very. Tap. Best. Tap. One.

And you are it!

Whatever game we were playing, we’d take off like little rockets, leaving the chosen one in the dust. My shoelaces layered in dirt. Uniform skirt flying. I was very slow. I liked freeze tag the best.

But these rituals of taps and claps reminded me of something else, too. In The Clapping Song, Ellis gives us a set of instructions: Clap pat, clap pat, clap pat, clap slap, clap pat clap your hand cross it to your left side––but not every rhyme or song does that. Most are learned; passed on through oral tradition, memory, and patterns of participation.

I attempted to deepen my search, combing my mind for memories of songs and movement. When I found phrases that felt familiar, I looked it up. Through a Youtube video, I was able to recall “Twee-Lee-Lee”, and though the song was familiar, the hand movements I learned as a child weren’t as involved. Not to mention that fact my child’s mind had mushed all the words together, so I only remembered some lyrics and mostly rhythm.

“Twee-Lee-Lee” led me to Rockin’ Robbin which was extremely clear in my mind. (I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the very influential 1976 cover by Michael Jackson). I could see myself doing it on the tarmac parking lot of the catholic elementary school I attended.

As children, we subbed in lyrics from the chorus for something a bit more nefarious. It went something like this:

“Mama’s in the kitchen burning that rice, daddy on the corner shootin’ that dice, brother in jail ringin’ that bell, sister on the corner sellin’ street cocktail. Rockin’ rockin’ tweet tweet, I love the beat. Rockin’ rockin’ tweet tweet, I love the beat.”

I still haven’t been able to locate the source for that one. An early 2000s internet archive provides an old forum of people responding to the prompt of “80s Clapping Songs,” and it's the only place I’ve found someone else cite anything similar to the lyrics I know.

Often raunchy and full of double-meanings, most of us didn’t know what we were repeating, even as lyrics changed subtly over distance and time. I recall “Shame, Shame, Shame,” a clapping song that requires you to hold your hands together in prayer-position and slide them against your song partner’s before clapping your palms together with the opposite hand, being a particularly popular song. It's the only clapping song whose lyrics match with my memory and any forum I’ve found online.

The song talks about not wanting to go back to Mexico because there was a “big fat policeman” there to intimidate you. Particularly xenophobic and strange, my godmother balked when she heard my godsister and I rehearse it in the back of her car. “Do you guys even know what you’re saying?”

The answer was, well, no. We were more interested in rhythm and in navigating our growing worlds with a certain amount of cultural competence. Clapping songs initiate you into the know. I don’t ever remember learning a clapping song, I just remember doing it. You showed up, you stuck your foot in, and you picked the very best one. You follow the pattern of participation, you touch hands with a peer, you follow a beat, and get something out of it: self-awareness, cultural humility, motor skill retention, trust.

These games were physical, too. Clap your hand at just the right time. Be faster than the other person. Notice the nuance in the pattern. Create body percussion. Create memory. Create language.

All of this is just language creation and memory. Let’s take this back.

Drums were an essential part of the social and cultural fabric of West and Central Africa. Because drums were communication devices to specific groups of people, they often had a known, rhetorical impact; they are inherent to a group’s identity. During the trans-atlantic slave trade, these drums were forbidden.

In Body Talk: African Rhythm and Language through Body Percussion, Joseph Stewart writes, “Drum rhythms were such a cultural staple that when this instrument was stripped away by slavers, the rhythms were embedded in the physical bodies of enslaved Africans. Body percussion became a means of communication for enslaved Africans on slave ships.”

Watch sound become movement. Watch movement become memory. Watch memory become cultural. Watch it shapeshift and transform us. As Black people and through diasporic memory , body percussion became inherent to our survival and communication.

In Site of Memory, Toni Morrison writes, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back where it was.”

Body percussion became tap dancing. Tap dancing became Jazz. Jazz became everything.

Stewart continues in Body Talk: “From the 19020s to the 1940s, Jazz was shaped by various forms of body percussion, such as hand claps and foot stomping. These percussive elements were a communicative bridge between jazz drummers and tap dancers.”

So, as a child reciting rhymes and movements from memory alone, what comes from all this percussionist decisiveness, word-smith cosmogony, culturally significant education?

These days, I’ll stand in a circle with some rhythmically inclined homies and make something. We’ll sing anything. We are all participating. We are participation. “We goin’ to the store,” someone will sing. Someone else will tap. Someone will hum. Then, the humming person will harmonize. “Ain’t we on our way?” someone will call, and then we’ll begin again.

Me and my friends? We make future with a hint of jazz, some movement, and forgotten nursery rhyme.